In social movements, leadership is a contested term.

Many organisers avoid it altogether, wary of hierarchy and the risks that come with formalised authority. Years of confronting hierarchical organisations, charismatic-leader dependency, and informal yet unaccountable power have produced a justified scepticism toward anything that appears to centralise authority. In our Leaderful Organising work, we engage directly with these concerns. Building on frameworks such as Ella Baker’s group-centred leadership, we focus on what it takes to cultivate organisational cultures in which power is consciously distributed, accountability is embedded, and leadership is understood not as an individual attribute but as a collective capacity — sustained by appropriate structures rather than personal heroism.

Nevertheless, even groups that are explicitly horizontal generate roles of heightened responsibility. Certain individuals become the ones who hold strategic coherence, relational infrastructure, institutional memory, and the emotional texture of the group. They often do so without formal recognition, and sometimes while actively resisting the idea that they occupy a leadership position at all. Yet their influence is real, and their labour — frequently invisible — shapes the political possibilities and qualities of the collective.

We designed our recent Leadership Retreat for people with these kinds of experience: those carrying substantial responsibility, often without dedicated space to reflect on what it asks of them. Rather than offering them a skills-based course, we set out to create a structured while spacious environment for reflection, peer support, and honest examination of the assumptions and pressures embedded in movement leadership.

Why a retreat, not a training

We knew that these participants would bring significant experience and knowledge from their organising contexts. What they would lack was not information, but space to interrogate their own mental models, creative reflexivity and relational awareness. To question how to manage projection and pressure, how to balance holding others with care but also with mutual accountability.

A retreat format allowed us to shift from delivering content to enabling participants to surface and explore aspects of their experience already present but rarely examined in the rush of day-to-day activism. It also meant we could focus on meeting them where they were, rather than having to work to a predefined agenda.

This approach was grounded in a core assumption: that the effectiveness and resilience of social movements are shaped not only by strategy, but also by the internal cultures, habits, and invisible beliefs, carried by everyone, but especially by those in positions of responsibility or influence. Creating conditions for people to reflect on these deeper layers — individually and collectively — was central to the rationale for this retreat.

How we structured the time

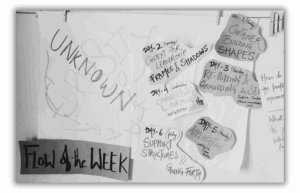

We intentionally reduced the pace and density of sessions and content, as compared to our usual training rhythms. Each day began with quiet awareness practice, followed by individual exploration of thematic questions. Participants could choose different modes — writing, movement, audio-guided reflection, crafting, or simple contemplative time in the “bath of possibilities” — depending on what enabled them to be most present, resourced and available to their process and experience.

Late morning sessions shifted to collective exploration. Using a mix of methodologies, including holistic approaches designed to bring a broad range of capabilities and senses online (eg. movement, sound, image work, theatre-based techniques, and embodied sculpturing/proxemic exploration), we supported the group to draw out patterns, contradictions, and insights from their individual reflections.

The early days focused on broader questions around leadership in movements:

- What meanings and assumptions do we attach to responsibility and influence?

- How do we navigate power and rank within groups?

- How do our socialisation and systemic conditions shape the way we step into or resist leadership roles?

After a mid-retreat period of rest and unstructured time, we moved into more applied work.

Participants brought real challenges into Troika-style peer consultations and collaborative mapping, allowing the group to learn through concrete case studies, rather than abstract theory.

We marked the beginning and end of the retreat with simple rituals oriented around three core principles — Curiosity, Solidarity, and Embracing the Unknown. This framed the retreat as a temporary community with shared commitments which we could return to as touchstones throughout, and supported the transition towards bringing the learning back to home contexts.

What emerged

A key outcome was the recognition of common pressures across very different organising contexts. Participants valued being in a space with others who understood the demands of long-term responsibility, and who could speak openly about the complexities of holding power while trying to avoid reproducing harmful dynamics.

Mara Clarke, co-founder of Supporting Abortions for Everyone – SAFE, has subsequently explained:

“attending the ULEX leadership retreat was life changing. I arrived exhausted and hesitant; I left with clarity, confidence, and tools that have transformed how I lead. Six months later, I am still drawing daily on what I learned—on strategy, prioritization, resilience, and narrative framing. The retreat shifted my organisation’s direction in ways that will increase our impact while using fewer resources. It also helped dismantle years of imposter syndrome in a single week—something no other training has ever achieved for me.»

Alongside this, the retreat surfaced learning for the facilitation team. Particularly that dynamics around race and power were present in the group but only articulated at the very end. This raised important questions about the balance between giving the group responsibility for its own relational environment and the facilitator’s roles in actively naming or intervening around systemic dynamics. The retreat format often creates different expectations from a formal training – for facilitators and participants – and navigating this distinction is an important area of reflection for us, going forward.

Reflections on the format

The retreat reaffirmed the value — and challenge — of creating learning spaces that question the balance of the skills-based, tool-oriented with the more unstructured or contemplative. When a group takes more ownership of its own learning, facilitators need to stay highly attentive and grounded, able to respond to what emerges rather than managing a predefined agenda. This was enjoyable, and challenging for us, in a different way.

We also grappled with the tension between rest and challenge. Participants were already stretched by demanding political and organisational contexts. Determining when to invite people into deeper inquiry and when to prioritise recovery required ongoing sensitivity and judgment.

Despite these complexities, the retreat showed the importance of creating spaces where movement organisers can reflect on the internal dimensions of their work, away from the constant urgency and task-orientation that often dominate movement life.

Towards more reflective movement cultures

What emerged most clearly in the final days of the retreat was a shared recognition of the pressures attached to occupying responsibility in contexts where leadership is both necessary and contested. Participants described navigating a contradictory position: required, in some way, to hold strategic coherence, emotional labour, and day-to-day continuity, while simultaneously expected not to appear as though they were leading. Without formal structures of mentoring or accountability, many had internalised the idea that they should be competent across all domains, and that any misstep would invite criticism rather than support.

Encountering peers who were grappling with the same tensions shifted the frame. It allowed for a more matter-of-fact appraisal of the work — its complexity, its affective load, and its political stakes — without the intensity that often accompanies leadership roles in organising work. This recognition functioned as a kind of calibration. People could see their efforts in proportion, neither inflated nor diminished.

This is directly relevant to the broader project of building leaderful movements. Distributed leadership is not only a structural pattern but a cultural and psychological one. It requires people in positions of influence to be able to examine how power operates through them, how group hopes and anxieties can accumulate around their role, and how communication and conflict are shaped by these forces. Developing this capacity is central to modelling reflective practice and fostering organisational cultures that can share power with integrity.

From this perspective, the retreat was not simply a pause from organising, but a component of it. It created the conditions for a more grounded understanding of how those carrying responsibility in movements might continue to do so without isolation, defensiveness, or the expectation of flawless competence – towards more resilient and distributed forms. Investing in these kinds of reflective spaces continues to feel so important to the development of movement health, effectiveness and longevity. We look forward to doing this again.