In Sweden, four activists who attended a training at Ulex launched a Resilient Movements project on their return. They speak about the negative impact of productivity standards on activist culture, and how social movements can become more resilient through daring to break silence around burnout.

By Valdemar Möller

Olivia Linander participated in a course at Ulex in 2016 before bringing tools of regenerative activism to launch the organisation Resilient Movements in Sweden. Photo: Helen Angelova.

Two days before this interview, Lanja Rashid and Olivia Linander – who run Resilient Movements (Resilienta Rörelser) together with Sam Lindskog and Johanna Lundström – held a 4 hour workshop on Sustainable Activism as part of a Radical Book Fair event in Sweden. Speaking about the event, Olivia says she was grateful to have had a substantial amount of time to address a subject that gets relatively little air time across social movements, despite stress and fatigue being commonplace in many organising circles.

Still, four hours is relatively short in comparison with the ten days of immersive training that the Resilient Movements team completed with Ulex in 2016, the starting point for the birth of Resilient Movements. Prior to this, Olivia herself had been suffering with burnout from her involvement with the climate movement during a particularly intense period in 2015.

“Following on from 2015 I was on sick leave for three months,” she says, “and then went straight onto my first course at Ulex in the autumn of 2016. I received a lot of helpful support and resourcing when I was there, and felt much stronger on my return”.

An easy slide into negative patterns

The course that Olivia participated in was part of a programme of trainings Ulex hold to support social movements to become more impactful and influential, whilst also increasing movement capacity and resilience.

“Before I left the training,” Olivia explains, “I asked the Ulex team how many Swedes had been there before and they told me I was the first one. I said that they could get in touch if they wanted to reach more people in Sweden and a year later we started a partnership training project together with an intersectional movement for women and non-binary people in Sweden called Streetgäris”.

Following on from meeting at Ulex, Lanja, Sam, Olivia and Johanna decided to start Resilient Movements. Lanja had also been on the road to exhaustion through her activism, but through the tools and practices she learned at Ulex she felt resourced and better equipped to continue. “The course helped me a lot,” she explains, “I learned new ways of thinking about and approaching activism.”

However it’s been a few years now since Lanja participated in the trainings and she stresses that it is easy to forget some of the key learnings and get carried away again with the all consuming nature of activism. “There are key questions that arose on the training that are necessary to constantly be reminded of,” she says “as after a year or so you might find yourself stuck back again in the same negative patterns. Continuing to talk about these issues through our work with Resilient Movements helps remind me of where I’m going and where I want to be.”

Olivia Linander (left) and Lanja Rashid (right) run the project Resilient Movements together with Sam Lindskog and Johanna Lundström. Photo: Private.

Making the personal experience collective

According to Lanja and Olivia the first step in making activism more sustainable is to actually carve out the space to start talking about it.

“We see that there are many people with personal experiences and problems to share,” says Lanja, “and that these often extend beyond the personal and occur as patterns within and across our organising circles and movements. So we try to take these personal experiences and turn them into collective experiences. Because if we are to succeed with finding solutions to these problems, we must do so in our groups.”

We need to talk about burnout

Within many organisations there is often a culture of not wanting to talk about issues such as stress and burnout, an issue that Olivia feels sits central to the health of our movements.

“It is a problem in so many organisations,” she says “but even if the subject gets raised, then often it stops at the talking level whereby people say “this is what we should think about” instead of discussing action that they can actually put into practice. It lands easily on an individual level, but it is not always possible for everyone to handle it by themselves. Or it ends up with a Board that decides how to take care of it. But we believe in order to really meaningfully address burnout that everyone in the organisation needs to be involved.”

Challenging the productivity norms that govern our thinking

Speaking about productivity norms that are active in society, Olivia continues to talk about how these same norms are reflected in activist and social change movements.

“That can be easily overlooked,” Olivia says, “especially when one is in a context that is system-critical, which means it can be difficult to talk about how these structures also exist within ourselves. It is a long-term job to become aware of them and then train them away.”

Lanja continues: “We are all children of a productivity society where we’re taught that things should go fast and you should do as much as you can, that you should be perfect and make everyone happy. It affects us both as individuals and as groups. In addition we now have a stress norm, which according to recent study shows that young people now gain a kind of status in being stressed because it shows that you have a lot to do and if you have a lot to do, you are an important person! These are standard norms and behaviours within the walls of many social change networks and organisations.”

How this shows up in behaviours within social change settings, Lanja and Olivia explain, is that people feel that they need to apologise when they say no to a task, or need to justify taking a break from activism. “This in itself is a sign,’ Olivia explains, “that we have norms and expectations in place where we’re not being so kind to one another.”

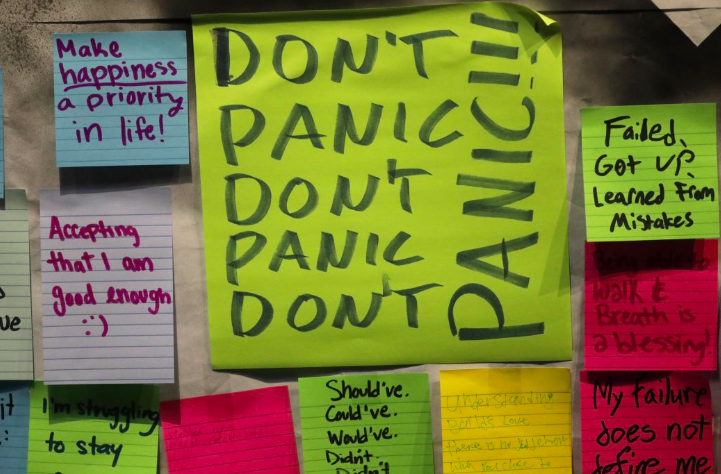

As an activist, Lanja and Olivia say, it is easy to succumb to the demands that are shaped by productivity norms in society. Photo: Rick Browner / AP.

How constructs of time fuel unhealthy productivity

Olivia believes that many of the issues inherent within productivity are also related to how we view the concept of time, another subject which was unpacked and explored during the Ulex training. “The usual way of perceiving time is as a linear concept where everything develops through moving forwards. Either we are moving towards some total victory or we are heading towards the end of the world.”

Olivia advocates that instead of this standard narrative there could be more supportive ways of resourcing social change work by opening up to a more circular way of thinking about time, where we accept that struggle in various forms has always existed and will always exist, and that even if we win some victories, new challenges will always arise.

In addition to stress and demands for success, the trainers at Resilient Movements have also witnessed that political struggle is often characterized by a sense of duty and guilt instead of desire and hope, which further increases the risk of burnout and people having to drop out of activism. Olivia says that this is not only a great loss for individuals but also for social movements in general. “When people break down this makes us weaker as movements. We lose in number, but also in diversity, experience and power.”

“If we change our way of thinking about time, struggle and gains,” she explains, “we can become so much kinder to both ourselves, and to our movements.”

This article was originally published on Landets Fria on October 6, 2020. Written by Valdemar Möller. Link to original article here.

More information:

Resilienta Rörelser – Resilient Movements, Sweden

READ ON: Sustaining Resistance : A Story of Regenerative Organising »»»